Serious Meningococcal Infections

ULTOMIRIS, a complement inhibitor, increases a patient’s susceptibility to serious, life-threatening, or fatal infections caused by meningococcal bacteria (septicemia and/or meningitis) in any serogroup, including non-groupable strains. Life-threatening and fatal meningococcal infections have occurred in both vaccinated and unvaccinated patients treated with complement inhibitors.

Revaccinate patients in accordance with ACIP recommendations considering the duration of ULTOMIRIS therapy. Note that ACIP recommends an administration schedule in patients receiving complement inhibitors that differs from the administration schedule in the vaccine prescribing information. If urgent ULTOMIRIS therapy is indicated in a patient who is not up to date with meningococcal vaccines according to ACIP recommendations, provide antibacterial drug prophylaxis and administer meningococcal vaccines as soon as possible. Various durations and regimens of antibacterial drug prophylaxis have been considered, but the optimal durations and drug regimens for prophylaxis and their efficacy have not been studied in unvaccinated or vaccinated patients receiving complement inhibitors, including ULTOMIRIS. The benefits and risks of treatment with ULTOMIRIS, as well as those associated with antibacterial drug prophylaxis in unvaccinated or vaccinated patients, must be considered against the known risks for serious infections caused by Neisseria meningitidis.

Vaccination does not eliminate the risk of serious meningococcal infections, despite development of antibodies following vaccination.

Closely monitor patients for early signs and symptoms of meningococcal infection and evaluate patients immediately if infection is suspected. Inform patients of these signs and symptoms and instruct patients to seek immediate medical care if they occur. Promptly treat known infections. Meningococcal infection may become rapidly life-threatening or fatal if not recognized and treated early. Consider interruption of ULTOMIRIS in patients who are undergoing treatment for serious meningococcal infection depending on the risks of interrupting treatment in the disease being treated.

ULTOMIRIS and SOLIRIS REMS

Due to the risk of serious meningococcal infections, ULTOMIRIS is available only through a restricted program called ULTOMIRIS and SOLIRIS REMS.

Prescribers must enroll in the REMS, counsel patients about the risk of serious meningococcal infection, provide patients with the REMS educational materials, assess patient vaccination status for meningococcal vaccines (against serogroups A, C, W, Y, and B) and vaccinate if needed according to current ACIP recommendations two weeks prior to the first dose of ULTOMIRIS. Antibacterial drug prophylaxis must be prescribed if treatment must be started urgently, and the patient is not up to date with both meningococcal vaccines according to current ACIP recommendations at least two weeks prior to the first dose of ULTOMIRIS. Patients must receive counseling about the need to receive meningococcal vaccines and to take antibiotics as directed, signs and symptoms of meningococcal infection, and be instructed to carry the Patient Safety Card at all times during and for 8 months following ULTOMIRIS treatment.

Further information is available at www.UltSolREMS.com or 1-888-765-4747.

Other Infections

Serious infections with Neisseria species (other than Neisseria meningitidis), including disseminated gonococcal infections, have been reported.

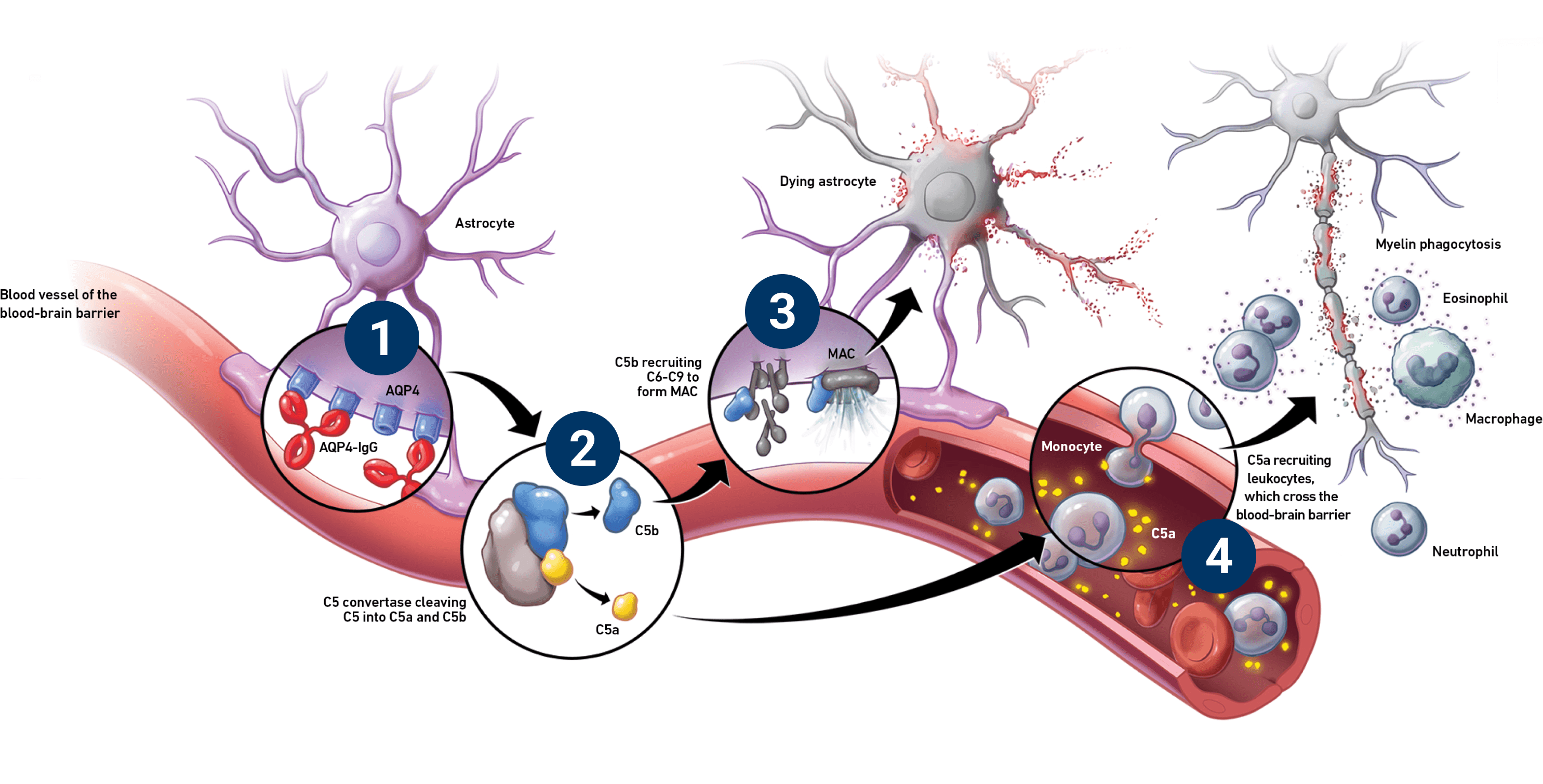

ULTOMIRIS blocks terminal complement activation; therefore, patients may have increased susceptibility to infections, especially with encapsulated bacteria, such as infections caused by Neisseria meningitidis but also Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and to a lesser extent, Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Patients receiving ULTOMIRIS are at increased risk for infections due to these organisms, even if they develop antibodies following vaccination.

Thromboembolic Event Management

The effect of withdrawal of anticoagulant therapy during treatment with ULTOMIRIS has not been established. Treatment should not alter anticoagulant management.

Infusion-Related Reactions

Administration of ULTOMIRIS may result in systemic infusion-related reactions, including anaphylaxis and hypersensitivity reactions. In clinical trials, infusion-related reactions occurred in approximately 1 to 7% of patients, including lower back pain, abdominal pain, muscle spasms, drop or elevation in blood pressure, rigors, limb discomfort, drug hypersensitivity (allergic reaction), and dysgeusia (bad taste). These reactions did not require discontinuation of ULTOMIRIS. If signs of cardiovascular instability or respiratory compromise occur, interrupt ULTOMIRIS and institute appropriate supportive measures.

Most common adverse reactions in adult patients with NMOSD (incidence ≥10%) were COVID-19, headache, back pain, arthralgia, and urinary tract infection. Serious adverse reactions were reported in 8 (13.8%) patients with NMOSD receiving ULTOMIRIS.

Plasma Exchange, Plasmapheresis, and Intravenous Immunoglobulins

Concomitant use of ULTOMIRIS with plasma exchange (PE), plasmapheresis (PP), or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment can reduce serum ravulizumab concentrations and requires a supplemental dose of ULTOMIRIS.

Neonatal Fc Receptor Blockers

Concomitant use of ULTOMIRIS with neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) blockers (e.g., efgartigimod) may lower systemic exposures and reduce effectiveness of ULTOMIRIS. Closely monitor for reduced effectiveness of ULTOMIRIS.

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

Pregnancy Exposure Registry

There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to ULTOMIRIS during pregnancy. Healthcare providers and patients may call 1-833-793-0563 or go to www.UltomirisPregnancyStudy.com to enroll in or to obtain information about the registry.

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. at 1-844-259-6783 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.